Micro Corruption Walkthrough (A Series)

by

Micro Corruption is an Embedded Security CTF found here. The basic narrative behind the CTF is that a series of warehouses spread around the world are protected by a Bluetooth-enabled deadbolt lock. These deadbolts can only be unlocked with the correct credentials supplied via the manufacturer’s mobile app. Our team wants to steal things from the warehouses and we were rightly left off the authorized access list. Our goal is to find some input (it might even be the password) that unlocks the lock and allows our team entry.

The challenge in the CTF:

Using the debugger, you’ll be able to single step the lock code, set breakpoints, and examine memory on your own test instance of the lock. You’ll use the debugger to find an input that unlocks the test lock, and then replay it to a real lock.

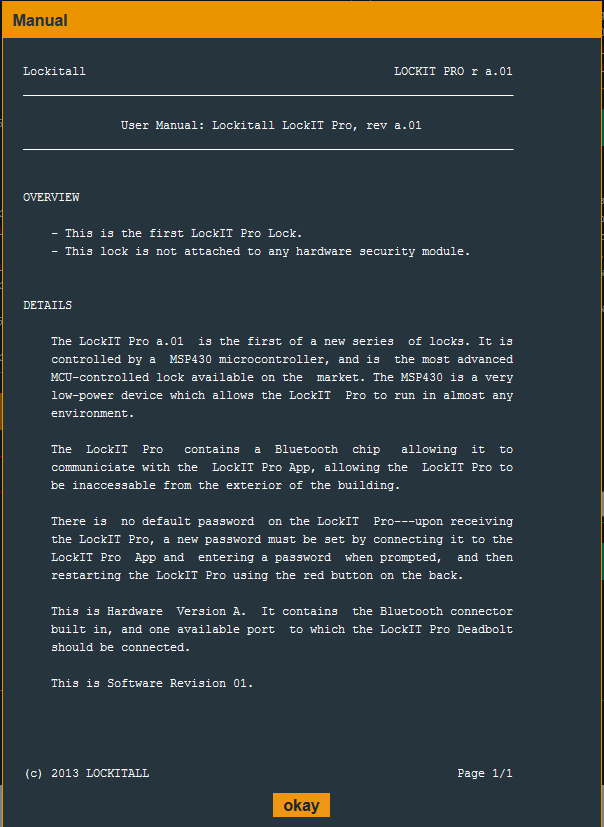

The lock is built on the MSP430 microcontroller and a lock manual is provided.

This series will be my walk through of how I approached and hopefully solved each lock.

We’ll start with level one - New Orleans

Walk-throughs of the other levels can be found:

| Sydney | Hanoi | Cusco |

New Orleans

Each level in Micro Corruption begins with a pop-up showing the release notes of the latest version of the lock. These notes can provide helpful hints on the types of security the developers may have included.

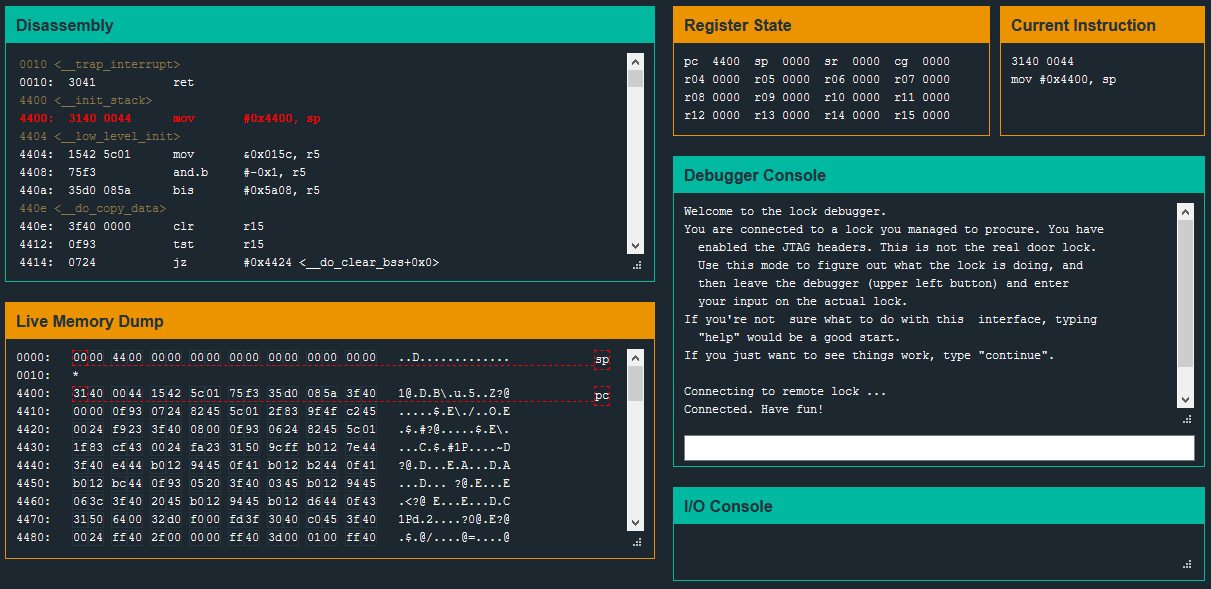

The debugger window consists of six sections - a Disassembly window, a set of registers, the current instruction, a Live Memory Dump, and I/O Display and a debugger console.

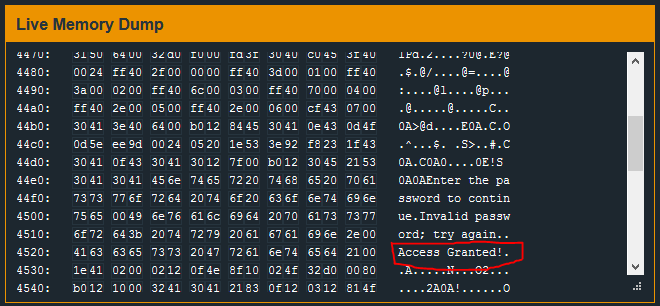

In the Micro Corruption tutorial, the password for the test lock was stored clearly visible in memory. So for level one, as a starting point, I begin by scrolling through the Live Memory dump window to see if there is anything obvious.

I see strings “Access Granted”, “Invalid Password”, and other terminal output - but nothing that is obviously a password.

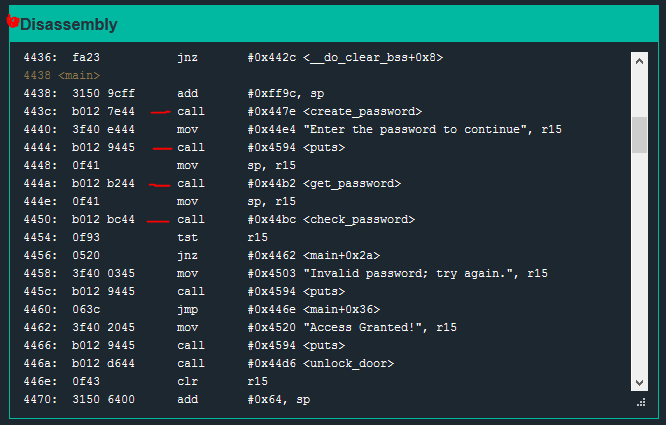

Next, I scroll through the Disassembly window looking for the <main> function. I will scan through <main> and look for all of the ‘call’ instructions to get a general sense of the program flow.

The first few calls are:

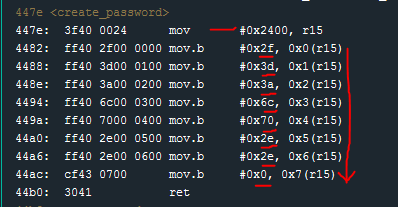

call #0x447e <create_password>

call #0x4594 <puts>

call #0x44b2 <get_password>

call #0x44bc <check_password>

create_password seems interesting! I scroll further through the Disassembly window looking for the create_password function.

The first instruction moves the literal value #0x2400 to r15. The subsequent instructions (mov.b) move literal byte values to some offset of the value stored in r15 (0x2400).

Because these byte values are clearly visible in the disassembled instructions we could copy them down and convert them manually from the ASCII chart.

0x2f -> "/"

0x3d -> "="

0x3a -> ":"

0x6c -> "l"

0x70 -> "p"

0x2e -> "."

0x2e -> "."

0x0 -> NULL Terminator

The converted string: /=:lp..

For a string 7 bytes long (8 with the null terminator) the manual work isn’t a big deal. If this password were longer or there were some sort of decryption loop, a better approach would be to let the debugger do the work. Work smart, not hard!

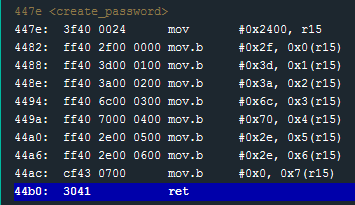

I will place a break-point at the end of this function (#0x44b0 ret) and allow the program to run up to the break-point.

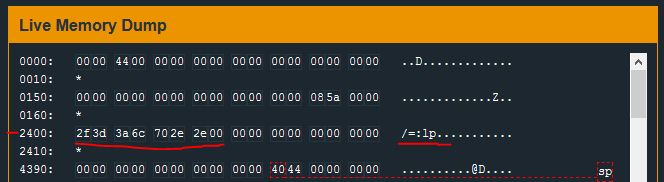

Once the break point is hit, I will check the Live Memory Dump to see if there is anything like a password at memory address 0x2400.

The break-point is hit and, at the memory location 0x2400, ascii characters are found. ASCII strings are terminated by a null character \x00 - so I will copy all the bytes leading up to the first \x00 starting at #0x2400:

/=:lp..

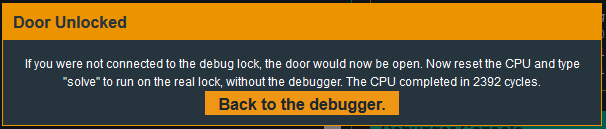

I will let the program continue running and use this string when prompted for the password.

And voila!

For a walk through of the next revision of this lock, click here

tags: